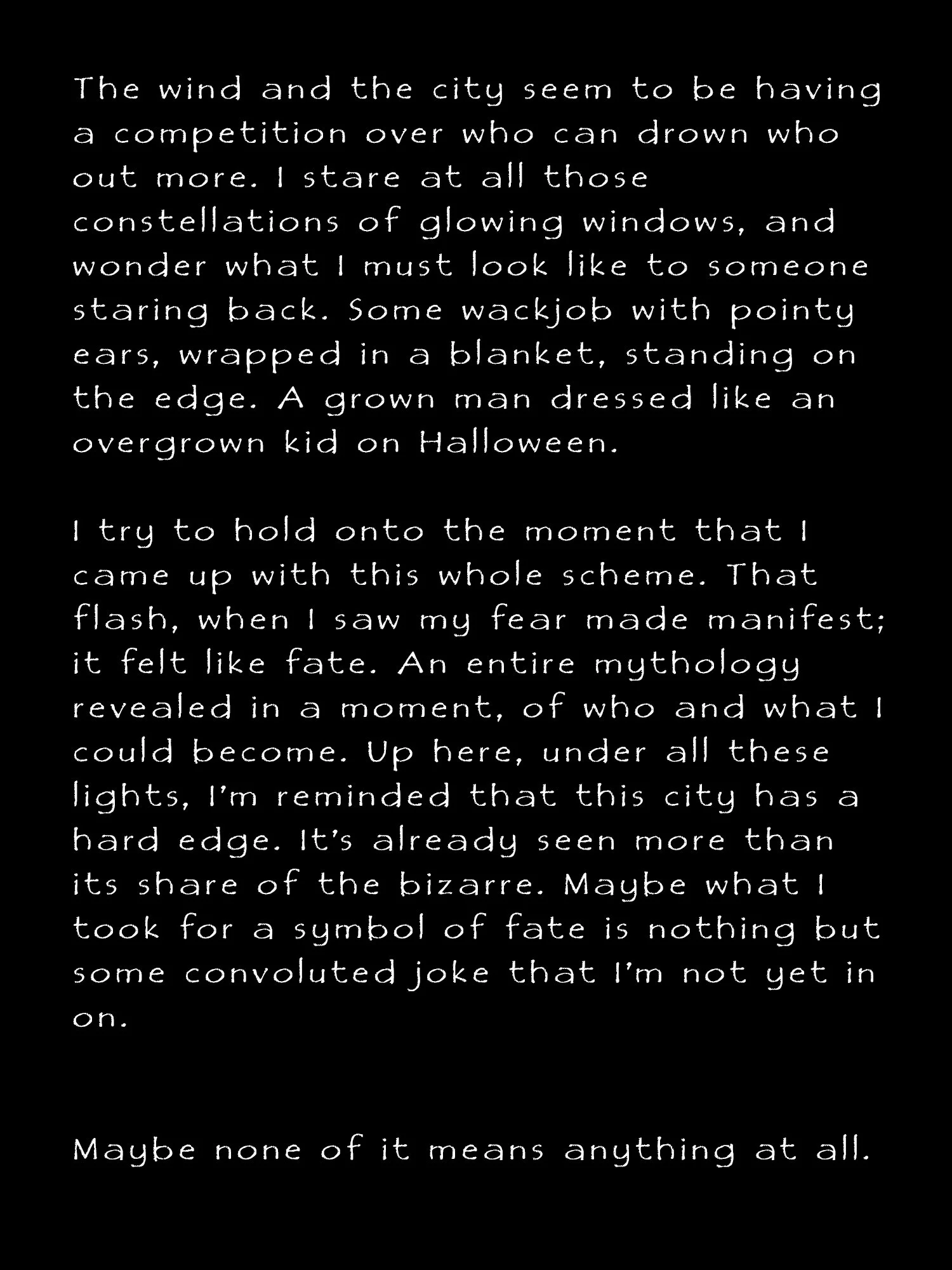

laughing with the storm presents…

ISSUE 001

THE LOW HANGING FRUIT EDITION

Featuring stories and art by:

• V.M. Collins • Drea George • Wyatt Hall • T.M. Hogeman •

• Sebastian Salgado Flores • Elissa Barrett Cohn •

A Few Notable Locations of the Dragon Smidge’s Journey Across the Sea

V. M. Collins

It takes ages to make a dragon. First, a land must be cursed from some long ago and forgotten catastrophe and, second, a gold mine in that cursed land must be mined to exhaustion. Once this is done, that last nugget of gold in the blasted earth will rise up into its uncanny second life as a dragon.

It takes even longer for a dragon to die. For they must retrieve all the gold that had already been mined before their birth. Only then may they finally lay themselves back down to rest in new earth. If the mines in that cursed land are vast—and they are—then the gold extracted from the earth will have spent decades being traded across the world, even into lands that have never heard of such a long ago curse, nor know of such cursed gold.

This search brings a dragon to many curious places. The dragon Smidge, for instance, first alighted on the shores of the land across the sea after they had exhausted their search in lands closer to home. And in this new land, Smidge has learned, there is a witch king, and that witch king has a vault full of wealth.

The witch king’s vault

Smidge, upon breaking into the witch king’s vault, quickly ascertained that the witch king did not, actually, have much in way of the material wealth that Smidge sought. The best that the vault could offer was a set of gold-gilt statues, cast in various gamboling forms of small dogs. Smidge, always keen for inspiration, reshaped their own small, golden body in imitation of the one they liked best, before consuming the original statue. The thin layer of gilding made for an unfulfilling meal.

But even in the face of such slight offerings, Smidge was not such a churlish guest as to leave without properly visiting with the rest of the treasures in the vault. This particular hoard was bored and lonely, and eager to gossip even as they bemoaned their neglect, feeling quite overlooked by the current witch king.

It did not take Smidge long to gather that the Baron of Larassal-by-the-Waters was considered the richest in all the land around these parts, and a rolled-up tapestry shoved into a corner insisted to Smidge that they had once even been a part of the Baron’s wealth. But then, following the chaotic aftermath of the tragic death of the former Baron, who had been sister to the current Baron, one thing had led to another, and the tapestry had landed here to moulder, and the tapestry was actually glad for it. It would rather, it confided to Smidge, be here rather than there, but it did rather regret no longer being on display.

Smidge gleaned that the current Baron was not altogether pleasant, especially towards reminders, as the tapestry seemed to be, of that former Baron. Even these neglected treasures had heard the rumors that the current Baron had arranged for her sister and her sister’s children to be killed so that she could inherit the title, and the wealth.

Smidge did not care for the intrigues of power, but they were interested in rumored wealth. Smidge would be visiting the Baron’s treasure chambers, of course, but more discreetly than in the form of a gold dog.

On the way out, Smidge bumped into the witch king in one of the side halls. “My apologies,” Smidge said, and trotted off, leaving a bemused figure behind them. The witch king had many magical experiments, and could not remember them all. Had there been an experiment to animate one of those cloying statues collected by her mother? A rousing success, were that the case. Worth investigating further.

Outside, and having already forgotten the encounter, the edges of Smidge’s golden form rippled and turned molten, and then Smidge dispersed into smaller forms of gold starling birds that flocked into the air. High on a cliff, the greater part of Smidge that they’d left behind—too much to be sneaking into vaults unnoticed—turned their attention away from the sunrise, and heaved themselves up in preparation of flight.

The whole horizon was open to Smidge, but they turned in the direction of Larassal and a baron.

Larassal-by-the-Waters

The Baron was away, when Smidge finally reached Larassal-by-the-Waters. The Baron’s manor was full of seething whispers, from every sideboard and candlestick and locked-up silverware. This was not a happy place, and the imprint of mistreatment of the people within the estate had laid itself thickly over every fine object that the Baron’s wealth had bought. But that was not enough to obscure the shining note of gold that sung through it all. There was a particular quality to that sound that told Smidge that some of it was Kiste gold: gold from their mother lode.

One of the tiny flea-forms that Smidge had sent—discreet—landed on a pile of fine golden rings. It would take a great many rings to truly make a discernible difference to the size of Smidge’s full form, but the flea-form had tripled in size by the time it had finished consuming those rings forged from Kiste gold, small bite by small bite. Smidge only grew when they ate Kiste gold; gold from other mother lodes could only be set aside in the event that Smidge met another dragon some day.

The remainder of metal in the rings’ composition went down the flea-form’s gullet, and disappeared into the transitive property of a dragon. Which is to say, that what belonged to one form of Smidge belonged to them all. If any part of Smidge swallowed a treasure, then all other parts of Smidge could cough it back up.

Another flea-form searched elsewhere in the manor, discovering that the Baron’s vaunted treasures were primarily an armory of fine weapons. The weapons in the armory were rattled and angry at Smidge’s appearance, and they were not keen to share anything with a dragon. All Smidge managed to learn was that the Baron was away at a tournament, and what riled these weapons more than the presence of Smidge was that the Baron had not taken them to such an important tournament. These were treasures that were well-suited to the Baron’s hand, and Smidge left them all behind.

Yet another flea-form of Smidge slipped their way into a cupboard to alight on the rim of a teacup and have a chat with what turned out to be a rather terrorized tea service. The Baron and her husband had a habit of throwing things about, and many a fine cup had never returned to the cupboard at all. The teacups, being privy to many a conversation in the parlor, and not fond of the Baron at all, had a great deal to tell Smidge about the tournament.

It seemed the Baron had been scheming over tea, and she was going to trick the witch king at the tournament. Maybe even kill her.

“But the winner’s purse is gold?” Smidge pressed. The schemes of the baron and the witch king did not concern Smidge. Only the prizes that Smidge might be able to carry away concerned Smidge.

The winner’s purse was gold.

Cheered by this news, Smidge flew from the house. They were golden pinpricks sparking in the air as the sun hit them, and they caused a few servants to blink and take a second look as they flew overhead.

Before Smidge left for the promise of a gold purse at the tournament grounds, they visited the markets as a small horde of gold vermin. In the Larassal markets, Smidge found a few trinkets. They always did. There was also a cedar chest that they considered longingly, but it was not the right time to finagle the logistics of spiriting away such a finely crafted item to their hoard.

At one stall, Smidge heard a packet of letters crying out from where it had been hidden away inside a book. Upon inquiring for more details, Smidge learned that the letters desired to be returned to a rightful heir who had been betrayed and left for dead, their inheritance stolen. Smidge made no promise of who they would deliver the letters to, but deftly removed the packet from the book when the vendor was not looking, and left Larassal.

Rightful heir business could be a real slog, because even the documents—whether it was the true will or a counterfeit will, or a packet of letters hidden in a book—tended to lie outright to Smidge, depending on whose hand had penned them. But, Smidge rather thought, one had to keep busy, in an endless search like a dragon’s, and tournaments didn’t last forever.

The local castle beside the tournament grounds

The local lord who was hosting the tournament had a castle that stood between the seashore and the tournament grounds.

The first thing to do, of course, was to pay their respects to the fine prizes that had been set aside safely in this castle. Smidge split a small part of themselves off as a small golden lizard, while the greater part of themselves napped in the nearby sea, hidden by the waves.

Smidge was dismayed, then, to discover that all of the prizes to be doled out to worthy competitors over the course of the tournament, and which were currently kept under close watch by guards provided by the witch king, were counterfeit.

“The gold purse, too?” Smidge asked in alarm.

A ring of fool’s gold, set with false emeralds, was sheepish about being a fake, and answered Smidge readily, even as a pair of silver-plated goblets, masquerading as true silver, scolded the ring at admitting to the ruse so quickly.

The gold purse, too, was counterfeit. All part of the Baron’s plot, the ring admitted. It didn’t know where its true counterpart currently was. Beneath the waves of the sea, the greater dragonform of Smidge let out a long, sad sigh.

It was a great disappointment, but since it wouldn’t be long before the smaller valued counterfeits started to be handed out, outrage at the discovery of counterfeits could be sparked at any moment. And that kind of chaos could provide a great deal of cover to Smidge’s own movements.

The tournament grounds

The encampment at the tournament was crowded and boisterous. There was a ferocious pride here in the generations of metal handed down from parent to child. Wicked blades of steel whispered of the blood they had spilled, sturdy shields rumbled over every blow they had absorbed and which they were saving up to return in full measure one day, and many tokens fair murmured over quiet understandings and sweet moments.

Smidge slithered through the trampled grass. Every now and then, they tilted their head back, scenting the air for that elusive scent of value known only to creatures of gold.

Smidge never forgot the scent of what had once been in their hoard. They caught scent of one such item now, given many years past to a champion of many tournaments. Between the trace of real gold on the air and that scent of an old treasure, Smidge pursued the latter, skittering and bounding over the trodden grass and the dirt and skirted around tents, following that scent to the source.

Their lizardform pushed in through the tent flaps, and a familiar hand reached down to let Smidge scamper on. Smidge was lifted up so that they could see Idran’s face: familiar lines worn deeper into sun-aged skin; somber eyes that spoke of keen observation.

“If you’ve come for the winner’s purse, it’s all counterfeit,” Smidge told him, still gloomy over that fact.

If there were nothing here to win, then Smidge did not want Idran to compete at all. Idran grew older each time Smidge met him again, the years seeming to speed up. After the competitions, Idran slowed down more, overcome with the accumulated strain on his body.

“A disappointment,” Idran said, “but not my goal. I am here to help a boy who was left for dead reclaim his birthright.”

Smidge had a sudden misgiving. They had mostly forgotten the tapestry’s tale, but a chord of vague recollection seemed to be struck now, even as, safe in the belly of the greater part of Smidge hidden under the waves, the packet of letters they’d taken from the Larassal market lurched.

Mere moments later, the boy returned to the tent. Judging by the amount of mud that covered the boy from head to toe and the aura of wounded pride that collected around his hunched shoulders, he’d been on the losing side of some tussle or another. He had barely a glance to spare at Idran, instead sitting down sulkily on the tent cot, and letting a bag of equipment he carried drop carelessly to the floor with a clang and clatter.

Smidge could tell immediately that the equipment in this bag was as equally sullen as the boy’s demeanor. In fact, Smidge could pick up whispers from around the tent, all from items in the boy’s possession. Armor that did not want to fit right, a shield that wanted to shatter, a sword that wanted to fall out of hand. Idran had his work cut out for him.

“This is Mirn,” Idran said to Smidge. “I believe his cause has merit, but he’ll need a dragon’s armament to make it through. Can you help him?”

Merit meant that Idran had been promised sufficient compensation that it could lead to more gold for Smidge. Cause, however, promised to tangle Smidge up further with the Baron. For the packet of letters were crying out from within Smidge’s greater self: It is Mirn! The heir betrayed. Return us at last to his hand!

“That equipment doesn’t suit,” Smidge said to Idran, reluctant to offer anything at all to Mirn, and offering only because they knew Idran well. “Perhaps—”

Before Smidge could continue, Mirn was standing, and a sword tip was hovering over Smidge’s head.

“From whence witchery does this creature come?” Mirn demanded.

“From the Kiste Mine,” Smidge said. “As the gold was exhausted there, so were we born of the last of it.”

Mirn was silent for a baffled moment, with no recognition of what Smidge had said. “Then what are you?”

“A dragon, of course.” Smidge tasted the aura of the sword currently threatening them. “That sword will break in two, if you try it on us. We suppose we could exchange it for something sturdier.”

“That’s a dragon?” Mirn said, incredulously, but did let the tip of his sword lower slightly. And then, tone acquiring a great deal more suspicion, “We?”

“We’ll take whatever is equal to the payment,” Idran asked Smidge, ignoring Mirn. Idran set Smidge down, and gestured for Mirn to hand over a coin purse. Mirn had evidently come to trust Idran, since he handed over the purse. Perhaps he was expecting Idran to pull out just a few coins; he was certainly not pleased when Idran dumped the whole purse in a cascade of coins in front of Smidge.

“But—that’s all of it!” Mirn protested, moving to sweep the purse back up, only to be held back by Idran.

Idran held Mirn off easily, demonstrating deftly that Mirn did not have much by way of combat training. “Hold up there,” Idran told Mirn, unhurried. “A dragon is the best exchange rate you’ll ever get.”

Smidge sniffed through the pile of coins, sorting out the handful of gold coins, and chomping through them in a few bites each, to Mirn’s great distress. It was more than generous, though Smidge could sense a greater stash of gold coins hiding in Idran’s belongings.

Smidge calculated the amount they’d consumed, and then coughed up the equivalent exchange in silver coins. Smidge didn’t recognize the provenance of Mirn’s gold, which told them that there was a gold mine out there that they weren’t aware of. Perhaps some day, from that mine, a new sibling would rise.

But that was some future day. Today they skittered away with the gold, not keen to remain near Mirn. As they left the tent into the darkened campgrounds, they could hear Mirn demanding of Idran: “You help that beast?”

This was no different from Smidge’s usual practice for tournaments. Smidge was long accustomed to finding a few promising contenders and striking a dragon’s deal: to Smidge would go all the gold that the competitor might win, in exchange for aid via some artifact in Smidge’s hoard. It required care in the approach, and a particular type of mortal to assist a dragon in this endeavor. One might say that dragons found gold the most delicious of meals: they were born of gold, and ate gold to grow. One might say that a dragon was a wealth-killer, stealing valuable things wherever it flew and hiding it all away. There were only a few who might say that a dragon existed to wrest back from mortal hands that which had been so forcibly exhumed from the ground that had birthed the dragon.

Mirn was not the type of mortal that Smidge would have chosen for such a deal, but it was no more or less than Smidge’s usual practice when they returned from their greater self with an enchanted sword and buckler for Mirn. Less usual was the upset in the belly of the greater part of Smidge, where the packet of letters from the market at Larassal grumbled, and even more unusually, threatened to come back up. Smidge resolutely did not listen as the letters nagged at them, accusing Smidge of villainy for letting the Baron go free even one more day, when the rightful heir was right there, and need only be handed the letters, instead of follies like swords.

Smidge took rather more care to note the way that the sword they gave Mirn began grumbling almost the moment Mirn took it. But Smidge’s hoard was well-curated, and the enchanted sword was more professional than its wielder.

It was not long before Mirn was awarded one of the counterfeit silver chalices, for a fine victory in one of the bouts a few days later.

Mirn returned triumphant from the minor feast celebrating the day’s victors with the chalice in hand. The chalice’s quiet pride in its successful masquerade instantly turned to a sheepish silence after it realized Smidge was in the tent. The chalice recognized Smidge, even though Smidge had changed shape and assumed the form of a statuesque golden dog. Smidge had been telling Idran about what they’d been up to since the last tournament where they’d crossed paths, and had gotten all the way up to the witch king’s vault.

Idran was experienced enough to doubt the chalice instantly, and to test it without relying on Smidge. And of the three of them in the tent, only Mirn was shocked to learn that he’d been gifted nothing more than a silver-plated goblet.

“The witch king deceives us,” Mirn announced, appalled.

Idran had a great deal of patience, but not so much patience as to endure Mirn getting swept up in the hastiness of a righteous assumption. He asked Smidge, “Or is this the Baron’s hand?”

Because it was a direct question, and because it came from Idran, Smidge answered honestly. The truth of the counterfeits, at least. They said nothing of rightful heirs.

“This whole time you’ve known?” Mirn demanded. “A piece of information such as would bring unanimous support in my cause to bring down that wretched backstabber, and you have hidden it from us? What a deceitful creature dragons are!”

Mirn stormed out. Idran followed with a sigh, clearly realizing that Mirn was likely about to do something rash. Smidge followed Idran. Smidge was not accustomed to having to share their champion at a tournament, and it was clear that Mirn was not mindful of anything in his care.

Mirn was heading towards the Baron’s fine pavilion, but Smidge sensed a clamor in the opposite direction. Among that distant rumble, Smidge heard the low muttering of the Baron’s personal possessions, the rings and necklaces she was never without. Satisfied that Mirn would find an empty tent when he reached his goal, Smidge peeled off towards the witch king’s pavilion, which seemed to be the source of the noise. They found their suspicion confirmed: one of the Baron’s lackeys, also gifted a counterfeit prize, was angrily confronting the witch king from the front of a gathered crowd. The Baron watched from the side with a cruel twist to her lips.

The letters roiled in Smidge’s stomach, as if to add their clamor to the mix. Smidge had never experienced an item in their hoard simply refusing to stay down.

And the letters refused to stay down.

Smidge unintentionally staggered out into the crowd, gathering more and more attention as they tried to overcome the sudden nauseous roiling in their stomach.

An elderly voice cried, “Sire, it’s a sign! This is none other than the statue once gifted to your mother by the former Baron of Larassal!”

Smidge started heaving. Rather indecorously, they hacked up the packet of papers from the Larassal markets, right at the feet of what appeared to be a courtly official.

The official gingerly took the packet and held them up to the crowd, which had temporarily halted in its drama to observe the drunken lurching of what appeared to be an animated golden statue of a curly-haired dog. “A message!” The elderly man proclaimed. He opened the letter and perused. “My king! There has been great treachery by one amongst us!”

The packet of letters radiated smugness, having reached the place it most desired to be.

And without Mirn having to confront the Baron himself, the way was made smooth for him to reclaim his stolen title.

Smidge left the tournament behind them in disgust.

The plain beside the sea

Idran caught up with Smidge by the time Smidge had reached the local castle, and together they traveled from the castle to the sea and then along the shore. Idran took a slow and steady pace, following the sea and its foamy waves there. After tournaments, Smidge and their champion would part ways. It was not yet that time.

Smidge indicated where they should stop, and Idran dismounted from his horse, and the two of them sat, watching the waves crest. Over that horizon, there was another tournament ground much like this, where they’d first met.

By the time they’d met, though, Idran had not really needed Smidge’s aid to succeed at combat. But in that first meeting Smidge had seen the way that Idran looked at Smidge like they were a creature of thought and volition, and not what their shared language called a dragon: fugitive gold. An errant thing. The truer name for a dragon would be a wound in the world, from where they crawled out of land that had been blasted open, excavated and exhausted of its mineral riches with the tools that magic could bring to bear against the land: leaving gaping holes behind that never healed.

And now, so many years after that meeting, Idran still gave Smidge gold to exchange for silver, though he asked for no treasure in return. Idran set down a coin purse on the sand, full of the hidden gold Smidge had scented among Idran’s belongings, leaving it there for Smidge to eat and exchange. The coin inside was from the Kiste mine, old, very old, and delicious.

Because this gold came from a vein of their mother lode, they felt themselves becoming more complete as they ate it, chasing after everything that had been hollowed out from the ground they’d been born from. On the day they found all the gold that had been taken from their mother lode and claimed it all back, they would return to the earth to sleep, returned to mineral: the long life of a dragon. For Idran to have this gold told Smidge what Idran had not: that Idran was also ranging further afield to find coin purses that contained gold from Smidge’s lineage.

Idran was older, stiffer, pained in his movements. There were times that Smidge envied that mortals did not have to work so hard and for so long to reach death. But now Smidge regretted the threat of it over Idran.

What Smidge had was mineral life, magic life, the slow weathering, and grinding, and carving and chipping away. They wanted to be warm and hidden under the earth again, they wanted to be a wound in the world that was finally healed, after they had finally gathered all their gold and found some new ground hidden deep from mortal hands. It was a wearying journey ahead, with an end that could come the next day or in a hundred years. In that time, dragons encountered so much treasure. All things hoarded had to be passed on. That was a dragon’s wealth-killing: to disperse every treasure they’d ever gathered back out into the world.

The evening light was falling, and the gold was exchanged, and the moment was done—time for the parting of ways.

Under the sea, the greater part of Smidge opened a molten eye and yawned wide, satisfied. They reached out their massive claws and kneaded them into the seabed, in preparation of departure.

While Idran had gotten older, Smidge had gotten heavier with the weight of themselves. A tidal wave crashed over the shore from the water that the greater part of Smidge displaced as they rose up from the sea.

Once they reached the shore, they scattered into a herd of bright gold horses. They gleamed and raced joyously beside the incoming foaming tide. The setting sun across the water washed the scene in red light.

And then the horses scattered into birds, rising into the sky.

Far over the water, the sun glinted off a flock of innumerable birds that swept and arced through the air. For the briefest of moments, for those who were lucky enough to glance up at the right time, the golden birds flocked into the shape of a massive dragon, its wings raised high.

•

Fig 1.

Grease Pencil on Newsprint

Drea George

Fig 2.

Grease Pencil on Newsprint

Drea George

Sebastian Salgado Flores

Take Me To The River

By Wyatt Hall

A young man stood on the red clay bank of the river, tying his lure and adjusting his black rubber waders. His rod and reel assembled, he stepped out into the water, pole in one hand, ratty cap on his head, working his way to the deeper section where he knew bass would sit. His chest ached for a moment, and he stumbled a little. When he found smooth ground, he stopped, and looked about. With a curl in his arms, he flicked the lure into the darker shadows of the water. The fly landed with a plop, and at the same moment his heart seized in a vice.

Losing control of himself, the fishing pole dropped from his hand, sinking to the bottom. The man spasmed a few times, a little bit of foamy spit emerging from his lips, and he fell backwards into the river. As water rushed into his waders, air remained in the toes and heels of his boots and his torso floated on the water’s surface, his body arched like a bow. Once the ripples had subsided, his body passed downstream without a noise or so much as a bubble. What the young man knew, and what he thought he knew, ceased to be.

Above the corpse in the river, the sky showered the countryside with blue and white light. The sun beat down on the meadows nearby with numbing, sticky heat. From atop the red clay banks, one might have thought that the heavens had decided to paint a self-portrait on the glassy water. The body floated across the mirrored canvas like a drop of rain slipping down a windowpane. Far ahead, a hook in the valley walls lurched the river in some unseen, unnoticed direction.

With a splash, something shiny and scaled dropped from an overhanging tree branch into the water, not a hundred feet before the bend. Its sine-curved movements carried it towards the man’s body. Once the creature had arrived at the corpse, it slid onto the man’s stomach and stretched itself out. Against the black rubber of the waders, the thing seemed almost invisible, save for glimpses of its white underbelly, which it went great lengths to hide.

Around the bend, the water began to shimmer and splash from intervening rocks underneath the veneer of the river. A film of haze blanketed the sky, obscuring the sun’s edges. The rapids ripped a thin, frothy line into the sky’s already muddled picture upon the river. The young man’s body and its passenger hastened in their approach to the rocks as the water carried them forward. Passing over the rapids, the body slowed as it rubbed against the algae-covered stones, and halted its progress downstream. The snake that lay on the fisherman’s stomach formed a tight coil, awaiting something unseen and unheard.

Scrub brush near the far bank of the river began to crackle and shake. An old fisherman in stained denim overalls emerged from the bushes. His shoes flipped and flopped in tatters, and he took his time as he stepped down the bank and onto the shore. But the old man’s feet in their plastic casings seemed to know the stones, and the stones seemed to know his feet. His amble across the river seemed less of a walk, and more of a casual meeting between friends at work. When the old fisherman stood not five feet from the corpse, the thing on the body’s chest hissed in tones vile and natural.

“Scat, you little cretin,” the old man said.

The creature hissed again in its underbrush voice as if to assert that yes, indeed, this body belonged to it and it alone. The old man laughed in scorn.

“I don’t care what you think. It takes a flick of my wrist to send you somewhere less pleasant than here.”

The reptile spat its displeasure at the old fisherman’s feet and thrust itself into the rapids. Sighing, the old man turned his learned gaze upon the body.

“Wake up,” the old fisherman said. With a rattle in the chest, the young man awoke, his eyes crazed and red-rimmed.

“What happened?” the young fisherman said. “Where am I?”

“Downstream of where you were, though how far I couldn’t say.”

The young man sat up on the rapids, water pouring over his rubbery legs. “Thank you for getting me. I must have fallen asleep, I just had the worst dream, like something was dragging me down. My waders were filling with water, and I sank below the surface, but I couldn’t reach the bottom to kick up.”

“I’ve had that dream,” the old fisherman said.

The two men stared at each other, one with a taut, questioning face and the other with answers scrawled in the wrinkles.

“I don’t feel right,” the young fisherman said.

“Yep,” the old fisherman nodded.

“I really need to get back home. Becky’s eating for two, any day now she’s gonna pop. You know how it is when your wife’s pretty far along,” the young fisherman winked as he stood up. “Which way to Howardsville?”

The old man shook his head. “Sorry, son, but you no longer need to worry about that.”

“What?”

The two men stared at each other again, one bewildered, the other setting him straight with a long look.

“I don’t understand,” the young man said, somewhat unconvincingly.

“All I can tell you, is that you will in time.”

“But I have to go home. I have to make dinner for Becky, and prep the truck, and plan for the week, and…”

“Relax. We have people to look after her.”

“Who?” the young fisherman said. Frustration, confusion, and a blooming sadness colored his cheeks.

“Me.”

The old fisherman squeezed the young man’s shoulder, and with a flourish dove downstream, away from the rapids. The young man nearly dove in after him, but the older fisherman sprung from the depths as if to answer his questions again.

“You’re taking my place,” the older fisherman said. “When someone stops on the rapids, and there will be people, wake them up and help them off the river. Send them up the path,” the aged fisherman said, pointing to a dirt track on the riverbank that wound into the brush. The fisherman dove back under the water. The young man paused, wondering why the old fisherman seemed to be so much more agile in the water, though it somehow seemed right. The fisherman popped up one more time, and smiled a bit, the wrinkles gone from his eyes. Those eyes resembled his wife’s.

“When will I see you again?” the young man yelled to the now younger man.

“Couldn’t say,” the lad shouted. “Hopefully no time soon.” The man in waders somehow knew this to be true.

With a final splash, the child submerged. His feet kicked in the air long enough to flick aside a pair of ratty old river shoes, and he was gone beneath the surface.

The young man glanced at the line of rapids, and the path that met them at the near side of the river. “Always something to do,” he muttered.

* * *

“Where’s Tommy? I’m not delivering this baby without my husband!”

“Ma’am, this baby is coming no matter who’s here. Now push!”

A young woman shouted loud and long. In a rush of blood and refuse, a baby dove headfirst into life.

•

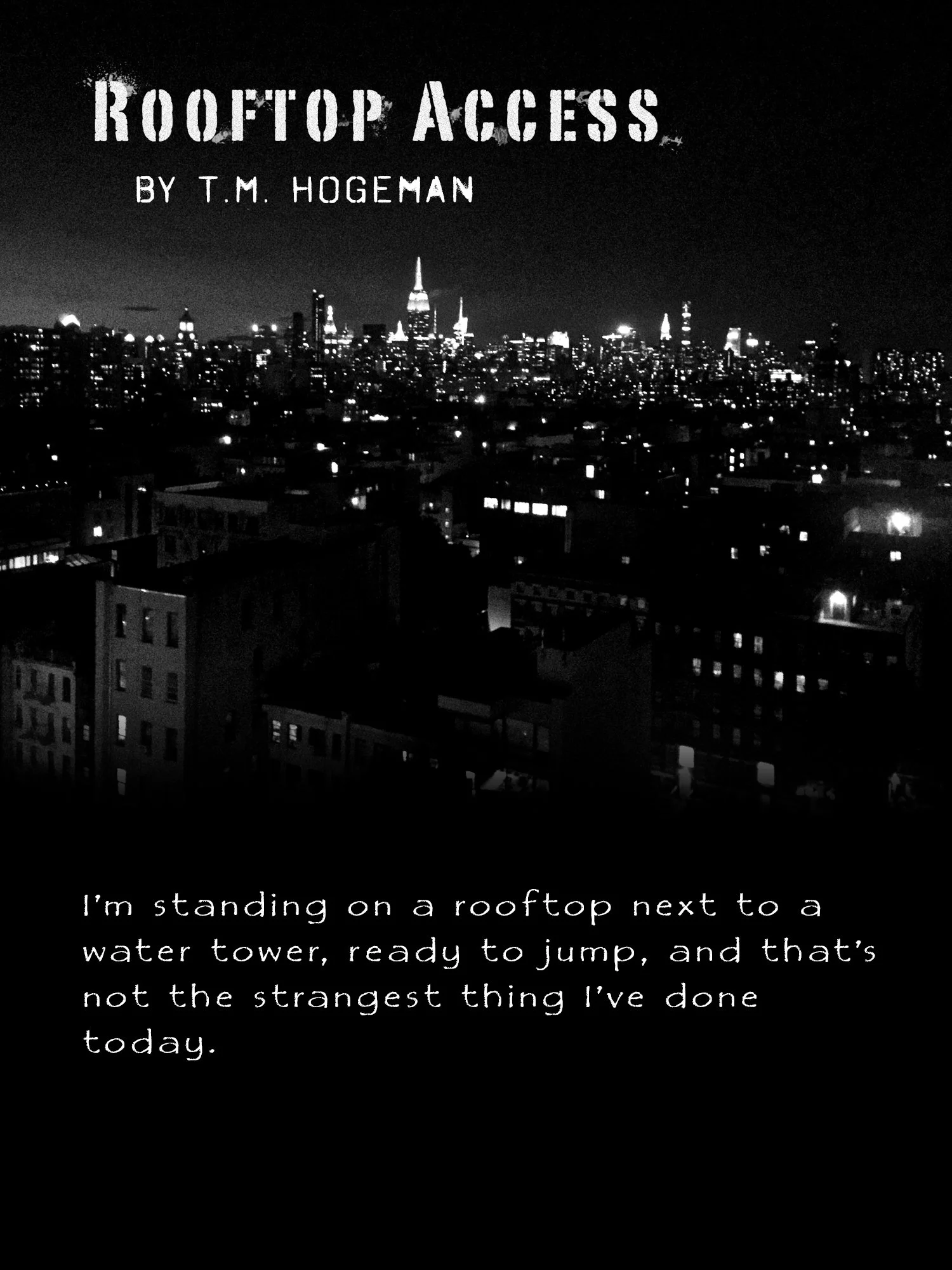

Breakfast Sandwich 01

T.M. Hogeman

Breakfast Sandwich 02

T.M. Hogeman

The Sea Above

By V. M. Collins

The sky god died while Inah was at sea, and the serpents mourned.

The sea-serpents had been favored children of the sky god, and had received many of her blessings. They used those blessings in her passing to call up massive storms that they thrashed and raged in, wailing out their grief. And in the long year after the sky god died, Inah’s ship was wrecked in one of the sea-serpents’ mourning storms. She survived, but Marden did not. So she came home, to tell old mother Hollis that her son was dead.

It had been many years since Inah had last seen Hollis. Not since she and Marden had first gone to sea. While Marden had gone home to visit over those years, Inah had always stayed back in the port cities, keeping herself as far from where she’d grown up as she could, putting roots down nowhere. And now Inah only finally returned once her last true tie to somewhere was gone.

Inah had never seen Hollis cry; today was no exception. Once Inah’s words had run dry, explaining how their ship had been caught up in a serpent-storm, and how the ship had cracked open, and Marden and many others had drowned before one of the sea-serpents had even noticed them and brought the survivors to safer waters, Hollis was stone-faced but dry-eyed. And once Inah’s inadequate words were done, and in that long silence while Hollis sat unspeaking, Inah felt once more untethered and adrift. The half-formed hope died away, that bringing Hollis this news would calm the ringing sense of emptiness that had followed Inah from the shore. She could not yet bear the thought of signing up for another voyage; she knew the once-beckoning horizon would feel empty if she went back.

“Grab the jar from the cellar,” Hollis said, at last. “Bring it to me.”

Inah knew which jar. She and Marden had often sneaked down to the cellar to stare at the crackling lightning bottled inside that glass jar: a gift of the sky-god’s breath given to Hollis when she was young. Perhaps it had been all those stolen moments in reverent silence in the presence of the sky-god’s blessing that had led Inah and Marden to the sea.

This was the first time that Inah had ever touched the jar, though, and her hands trembled as she carried it back to Hollis.

The lightning sat on the table between them, vibrant and crackling and wild in its fragile container. She felt different in its presence than she had as a child. Back then, the jar’s aura of power had given her the sense of clear skies without end, had made the air she breathed seem pure and clear. Now she felt instead the sharp edge in the atmosphere that precipitated a serpent’s storm, and she recalled images from the past year: bolts of light arcing through dark clouds, flickering over the shadowy serpents lunging from the water, jaws open wide as if they could roar louder than the thunder.

The lightning was supposed to be Marden’s inheritance. Hollis pushed the jar closer to Inah. “Take this to Lake Caervalon,” she told Inah. “Minna is there. She’s written, and tells me that the lake-serpent there is dying. Bring it to her.”

Inah was frozen in surprise, not sure what to address first—“You’re giving it away?”

“What peace can a dead god’s blessing bring any of us now?” Hollis said. “Minna has a need of it now. She joined the sky-god’s clergy after you left, you know. Marden would have given it to her. That’s what I think. But these old bones can’t make that trip anymore.”

A detour to Lake Caervalon would make no difference when Inah had not thought past what came after Hollis. Lake Caervalon was the greatest of the sky-god’s temples. It seemed fitting that Inah would only see it after its glory days of basking in the sky-god’s regard were gone. Of Minna, she felt no more than a flickering sense of recognition.

“I will do this,” Inah said. Hollis seemed satisfied. Inah had never known Hollis to give much praise, not to her sons, and never to Inah, the tag-along following her friend home. To be so entrusted with this lightning was one of those sparing signs of approval, and more than Inah had expected.

“Now, come,” Hollis said. “Tell me some more of my son, the things he didn’t write home about.”

* * *

The water of Lake Caervalon was said to be as clear as a blue summer sky, and even on the stormiest of days, the sky-god could be seen in the reflection of the perfectly placid surface of the lake.

This was the vision that Inah held in front of her on the long, uncomfortable walk on the unmoving ground. The further she walked from the shore, the more the missing sense of the sea weighed on her. It seemed an unreasonable burden of the land-bound, to have to affirm each day the direction they would take, and set themselves on it with each step after miserable step. She had relied on the tides and the winds to choose her course more than she’d ever admitted to herself before.

In the quiet of the evenings, she could not stop recalling that moment when Marden was torn away from the ship deck in that storm, torn away from her reaching hand, never to be recovered. Still saw the massive, scarred head of the sea-serpent that rose above the survivors in the eerie stillness of the morning after. How large would the lake-serpent of Caervalon be? She did not know what Minna wanted with the bottled lightning, but she found that thread of curiosity growing each day, pulling her towards Lake Caervalon even in the moments where she might have simply sat down on the road and let the hours pass in a blink. She had a sense that that she was on the precipice of some cavernous feeling that would not find any measures or limits; perhaps grief, perhaps anger, maybe despair, and that the only tether preventing her from falling into it was this pull towards Caervalon.

Yet the renowned lake, when Inah arrived at the lip of the Caervalon valley, was a milky white. She stared at this omen with dismay. Fouled water spoke of a foul temple, and surely it meant that there could be no life left in that lake.

The thought hit her harder than she’d expected. She reached in her bag to lay a hand against the cool jar that held Marden’s lightning. She felt the lightning in the jar crackle and pulse, just as the surface of the lake boiled and shivered in a familiar way. She knew what was coming a breath before a great serpent broke the water’s surface.

The relief that swelled through Inah at seeing the lake-serpent still living took her by surprise. She let out a sharp prayer of thanks to a god now dead.

* * *

The closer she got to the lake, the stronger the scent of rot hanging on the air became.

She did not yet want to enter the temple at the lake’s edge. Soon enough she would ask for Minna, and be faced with the question of where she would go next.

She heard chanting echoing out of the temple, the sound humming in her ears as she walked past the building to the pier, and then to the end of the pier, where the temple’s altar stood. She felt exposed, the wind cutting sharply through her clothes, but she felt more danger from the milky white water that gently lapped below her than she did from the serpent somewhere out in those waters.

She stared at the still surface of the water, repulsed by the milky white color and the stench, and willing beyond hope to see the serpent break the surface once more. The point of an altar like this, built out on the lake—or built on the deck of the ships she’d called home—was that supplicants could be balanced between the sky and clear waters. The sky could watch her, and the water reflect her back to the sky, with no hiding between the two of them. But that sense of observation was long gone; had dissipated after the sky-god’s death.

Moments, maybe hours, passed in a blink before she heard, distantly through her wandering thoughts, the sound of footsteps on the wooden planks behind her. She should turn, face whoever was approaching, but her body felt far away, unwilling to listen.

“What calls you here?” A voice from behind her, jolting Inah’s focus back to Lake Caervalon.

When Inah turned, she found a priest standing on the pier with her. Her black braid tangled in the wind. It took Inah a few minutes to recognize her. It was Minna, who had grown up in the same village. Minna was a few years older, and had taken her priest’s vows before the gods had died and upended all their lives. Inah’s strongest memory of the other woman was an old one: Minna’s giant eyes, peering over the window sill from her house while Inah and Marden took a short cut through her family’s back garden.

Those too solemn eyes were unchanged, squinting against poor eyesight. But Minna had finally grown into her face. There was something indefinably sharper about her now, though she still seemed to be eternally focused on something much further away than where she stood.

“Minna,” Inah said. “It’s good to see you here.”

It was good, to be honest, though Inah had not realized that would be the case until now. Minna was silent, and her flat gaze made Inah feel as if perhaps Minna didn’t remember her.

“It’s Inah,” she continued, a little uncertain now. “I grew up in the house next to you.”

“Yes,” Minna said. “I remember. How surprising, for us both to end up here.”

Minna said this with a measure of indifference and a sense that she was focused on something entirely unrelated to Inah. It was the same manner she’d had when they were younger. Inah had forgotten that about Minna, until faced with it again; there was something perversely comforting about finding this mannerism unchanged, even though Inah had once found it aggravating.

“Hollis sent me,” Inah said. “She said you’d written her to ask for her jar of lightning. She sent me with it.” Lastly, she added, perhaps to see if Minna—expressionless through her explanation thus far—would react: “Marden died.”

“I am sorry to hear that,” Minna said. “Marden had a heart for the serpents. I recall that.”

Minna meant that brief condolence; Inah had more experience now to recognize that. And even Minna’s small acknowledgment felt like more to Inah than anything Hollis had said, and Inah spoke without quite realizing how much she felt desperate to speak: “He said once, that he wanted to visit Caervalon. Meet the serpent here.”

“And would you like to?” Minna asked. “Meet the serpent?”

Posed to Inah like that, in Minna’s direct, indifferent way, like the answer did not particularly matter to her, Inah could not hide from a truth she had not recognized until then. She did. She did not know what she could possibly say to the serpent, she did not know what she would feel when the serpent rose above them, but there was something wild and tangled just under her breastbone that remembered that long-ago day when she’d seen her first glimpse of a sea serpent from the deck of a ship, under still-blessed skies. That moment of seeing the distant body of the serpent arcing out from the water, an impossible, endless leap before it glided back underwater. She and Marden had both stood in breathless awe. Marden had told her about Caervalon. Inah hadn’t said anything.

“Yes,” Inah said now. “I would.”

Minna held her hand out for the lightning, and Inah passed it over carefully. Inside the glass jar, snapping arcs of light crackled and sought for escape. The sky god’s own kiss—that’s what the serpents called this kind of lightning. Even after the god’s death, small wisps of her power still remained, not yet used up.

Minna set the glass jar on the altar. The altar was a simple wooden table, carved deeply with inscriptions and symbols, and deeply weathered from its time under the open sky, the wind, and the rain. As the jar gently touched the altar’s surface, the sky seemed to boom across the lake, and Inah felt the breath punched from her lungs. And yet, the world was calm, the skies open, no hint of dark clouds being summoned on the horizon.

It took a few minutes—long minutes, where the wind died and sound itself faded away, leaving her in a tight vortex of anticipation—before the water hissed and steamed around the columns of the pier. Slowly, a massive head rose from the lake before them, shedding water. The jaws of a serpent were long and fearsome, but this poor creature was missing most of his teeth, and Inah could see the milky white of his eyes—the same color as the lake—showing his blindness. The scaly hide of the serpent was ragged, patches of scales missing and displaying the fishy white flesh of the serpent’s skin. Inah knew that gills ran all along the body of the creature, and that he could hold his head aloft in the air for a long time without suffocating.

Facing a serpent like this, unarmed, unarmored, desperately vulnerable in her flesh and breakable bones: it evoked a tight mix of terror and awe in Inah, unbound to the decrepitude of the serpent.

“What moves you to call me?” the serpent asked. Serpents spoke through the water, the sounds vibrating out and thundering across the surface of the lake. It could be difficult to decipher words spoken on the high seas, but on the calm waters of the lake, they rang clearly to her ear.

“Some weeks ago, I wrote to a woman who you once gave a blessing of lightning, so that we could offer you a final gift of a cloud-burial. My request has been answered, and that sky-kiss has been brought by Inah, who stands here with me. Do you accept this blessing, and a cloud-burial?”

Inah had not known that about Hollis.

The lake serpent swayed, the water rippling and forming small tides around him as he moved. Inah saw his gills flare, and his tongue flicked out, as if tasting the air.

“I was placed here by the hand of the god who lived in the sea above, an age ago,” the serpent replied with gentle ripples of the lake. “I had never before known or felt the limits of this place as long as the sky was full of her blessing. But now I fade and the lake goes with me. Tell me, Inah who brings my old blessing back to me, what do you feel when you gaze upon this lake?”

Inah swallowed hard, but her voice was carried clean across the water to the serpent. “I think that the sea-serpents have a chance to grieve that you have been denied. I think this lake is too small for you.”

The serpent leaned in close to the altar, to the lightning there, and Inah saw his gills flare as if breathing in deep. He made a humming sound that reverberated through her chest, and made the glass jar vibrate.

After a long pause, the serpent said, “It would be my honor to accept. I am long past the need to grieve, but with such a blessing as this, my rotting corpse can be sent to the clouds to be buried there, and the lake cleansed. And so could future grief be averted.”

Then he was gone, disappearing back through the lake surface so smoothly that the water barely rippled.

That sudden absence felt as if all the air had been sucked down into the lake with the serpent, and Inah struggled to drag her next breath into her lungs, feeling winded.

Minna turned back towards the temple. “Come, then. The serpent dies and night will be here soon. Tomorrow, when his body floats up to the surface, we can begin.”

“Tell me of him,” Inah said, as Minna led her into the temple. Inah felt as if she stumbled across a gaping wound in the world. In the lake serpent, she had glimpsed something remarkable, just in time to see it depart from the world.

* * *

In the morning, it was as Minna predicted. The long, coiled body of the great serpent floated upon the surface of the lake, which had solidified into something like marble. The water was absolutely still, hardly water at all, anymore. Everything below was cut off from all that was above. A small pebble that Inah cautiously dropped onto the water did not sink, but remained on the surface.

Minna emerged from the temple, laden with supplies, while behind her came the other priests who shared the temple with her. There was a story, there, of how Minna had left the village and come here, and maybe she’d tell Inah, just as Inah might share her time at sea. The others cupped burning candles in their hands, and one of them handed Inah a censer to carry, incense smoking out and making her eyes water.

Inah had been instructed to stand behind Minna as she conducted the ritual. In days past, when rituals were performed, the world would still and silence around the altar–the sensation of a god’s attention turning towards them from far away.

Instead, today, they had only a petrified lake, a high keening wind, and a dead serpent. The words were the same, but they felt powerless.

Inah kept swinging the censer, right, up, left, her heart beating faster despite the dullness of the carefully cadenced words.

When Minna lifted up the jar of lightning, now suffused with a corona of a leashed storm, Inah’s hands trembled.

Her eyes watered, perhaps the incense, perhaps tears. Minna uncorked the glass jar, and a thunderous clap rolled out of the heavens, as seemingly endless amounts of lightning bolts escaped. Some bolts struck the hard surface of the water. Others skipped along the surface towards the body of the serpent, or rose straight to the sky.

Like a thin sheet of ice breaking, the crust on the lake surface cracked and broke, and the water sizzled as the lightning swept through it. The great body of the serpent was wrapped in bolts of light, and then–

The lake began to rain. First slowly, like mist, and then fiercely, drops of water rose from the lake, and then fell to the sky. In the storm that raged over the lake as it became the sky, Inah saw flashes of light, illuminating what could have been a serpent made of storm clouds, racing for the sea above.

In all her life, in all the years that the gods had actually lived, Inah had never seen such a testament to the mercy a god’s blessing could bring.

In the driving wind and rain, Inah stood, transfixed, until it was done. Until she could see Minna again, as drenched with the rain as Inah, until she could see all of the candles they had brought out still flaming.

Around them, for a moment, the world was perfect stillness. Then the lake moved again, the water lapping around the pier. The water was no longer milky colored, and had no more of that foulness. It was a clear lake again, placid, and the sun glinted off the surface.

One by one, the candles were released onto the water, where they would float until they burned out. When the last one was released, Inah turned to Minna.

She did not know what to say, and so said nothing, and instead watched as Minna knelt down and cupped some of the water in her palm. She let the water run out of her hand, and then stood, something settled and calm in her expression. She spoke to Inah over her shoulder. “It was good of you to come all this way.”

Inah stared down at her own hands, shaking, which were rough and callused and lined with scars. “What will you do now?”

Minna held out her hand, empty palm up, gesturing out to the lake. “Today, I will enjoy the view. Tomorrow, maybe there will be fishing. And the day after, well. Perhaps I can take a small boat, and see what lies on the far shore.” She paused, and her brow furrowed just slightly. “Or perhaps I will just take a short swim, and leave the boats to you.”

Perhaps. It seemed a very Minna thing to say, and nor did she seem to require a response. Instead, she slowly paced away down the pier, her head tipped up slightly. Inah stayed out on the pier after the others had trailed back in to the temple. She stared across the shimmering clear water, to where it glimmered and disappeared as it merged with the sky on the far horizon. Though she knew it would not happen, a part of her felt that any moment she would catch sight of a serpent breaking the surface along the far shore.

She stood there awhile, held between the lake and the sea above. A deep laugh from one of the priests carried from the temple. Misty serpents chased each other among the swiftly moving clouds. A soft breeze tugged gently at her, and although the sense of the sky-god’s regard was once more absent, what was left did not feel empty, either.

•

Drawing

Elissa Barrett Cohn

Fig. 3

Drea George

Shadow Box

Elissa Barrett Cohn

Fireplace Magic

Wyatt Hall

Julie pulled into the front yard of the cabin for what she hoped would be the last time. It was rustic, with bunks on a screened-in porch and an outhouse in a straight shot off the front door. It was co-owned by a friend who’d said she could come when she wanted and lent her a key that had long been forgotten. When she got out of the car, she paused to see if any of the lights of the other cabins nearby were on, or if she could hear anyone. All that greeted her was darkness and the burble of the river drifting by on the other side of the driveway. She pulled a headlamp from her jacket pocket and put it on. After grabbing her backpack, her cheap sleeping pad, and her bag of Chik-Fil-A, she headed inside.

Wooden slatted bunks covered the far wall inside, stacked three high. It was colder inside than outside, since no real sunlight hit the cabin during the winter days. Julie got the two shrink-wrapped bundles of firewood and the Firestarter log from the car and set to work building a fire. She set up a square frame of wood like a Lincoln log cabin. It only took her a minute to get the wood to catch from the Firestarter, as opposed to the first couple times she came here and spent hours using napkins, lighter fluid from under the kitchen sink, and green sticks from the back yard. Once the logs caught, she sat at the one table in the cabin in a rickety chair and ate her dinner, staring at the fire. She tossed the bag among the logs when she was done.

From her backpack, Julie pulled a small bottle of whiskey and a thin manila folder labeled “Rob”, and sat on the dusty floor in front of the fire, setting the two objects to the side. She’d noticed the second time she’d come to the cabin that fires talk if you get them going. They tell tales that you somehow already know. They snap and pop for emphasis, they chatter, they thrill or whisper as the story calls for. Julie had been mildly afraid of them before, but she liked fires now, and if she ever lived in a house she was going to have a fireplace.

After getting lost in the fire for a while, she opened the bottle, and took a swig. With a cobwebbed poker, she cleared out the center underneath the Lincoln lugs, creating an empty spot among the orange embers that glowed like an old oven. She flipped open the folder. On top was a picture of Julie grinning foolishly next to a handsome man with a strong chin and green, knowing eyes.

She took another drink and placed a log on the square frame. The picture in her hand had started to curl in the corners from years of being stuck on photo boards and in cramped drawers. Julie took a third drink and placed the photo in the niche ringed by embers. It curled in on itself like a hand making a fist. After several minutes, the picture was indistinct from the ash surrounding it.

Julie took another pull on the bottle and got the next item from the folder: a lease. She slowly undid the staples on the document and set them on the side of the fire. Page by page, punctuated by sips of whisky, Julie placed the lease of the apartment they’d had together underneath the log frame. Each page burned down to cinders before she rested the next one on it.

The last item she pulled out was a missing persons report. At the bottom, in the “department officials only” section, the status was labeled “resolved.” It had only taken three weeks for them to find him two states away, happy and healthy and married to another woman. A part of her wished the police had never found him, so she’d have been spared the knowledge that she was just a side piece. She placed the folder on top of the log frame, because that was all that was left.

When the center was nothing but ash, she took out a plastic mug from her backpack, as well as some herbs in unlabeled pouches. The side of the mug had a sloth hanging from a tree branch, with the words “Wake me when it’s Friday” written underneath. She measured out contents into the mug from each bag with a metal spoon: one teaspoon from the green, leafy herbs, two from the red berries, a half from the wispy yellow roots. With the ash pan next to the fire, she carefully collected the cinders of every item she’d burned and poured them into the mug as well. She ground them into a powder with the spoon, then spat in it twice and mixed it further. Finally, she poured half the remaining whisky in the mug and swirled it. Before she raised it to her lips, she checked the fire to make sure she’d cleared all the ashes of the objects out of the pile. Julie added two logs onto the fire, because this next bit was going to take a minute. She didn’t want the fire to be dead when she woke up. The comedown and the hangover were hard enough without waking up to a freezing room.

The logs aligned and the fire stoked, Julie put the mug to her lips and drank. It tasted like she was licking a burnt log covered in whiskey and moss and dirt. She gulped it down with a wince to be done with it and set the mug to the side. The fire snapped as she wiped her lips and rinsed her mouth out with a tiny bottle of Listerine from her pocket. It helped her not wake up with barbecue breath.

And so the waiting began. It only took a minute or so to kick in, but for that minute, everything became so loud. The creak of her body on the wood floor, the crackle of the fire, the breathing of the embers as they sucked in oxygen. Her chest bobbed up and down, knowing she wouldn’t be ready for it when it hit. Above the fireplace on the mantle, a spider was spinning its web spoke by spoke, and the web started spinning too, slowly like a clogged drain, until something unplugged from the pipes of her mind and the drain began to spin faster. The wall behind it started spinning too and now the whole room is spinning faster and faster like a tilt-a-wheel at a state fair and she has to lay down otherwise she’ll be thrown out of the room it’s spinning so fast and it’s so hot in here her clothes are off now and she’s lying on a bed, she’s giggling in his ear, he has her in his wiry arms and she knows he’ll never let her go. She pauses to breathe in his smell, to let it wash over her.

“What are you thinking?” Rob says, stroking her hair. He’s naked too, their legs intertwined.

Strings of warm yellow LED lights creep like ivy up the railings of her white metal bedframe. The bedframe bars are rounded and a little wobbly. Behind the frame is a large cloth mandala, red and gold and blue, with small holes burned in it from various misadventures. Between the lights, the mandala, and the hash, a halo forms around Rob’s head, slowly spinning. He looks like a saint. She moves her head back a half inch on the pillow and marvels.

“Just counting my blessings.”

“Can I ask you something?” he says tentatively.

“Of course.”

“And it’s okay to say no.”

“Just ask,” she says, cupping his chin with her hand.

Rob pauses, his green eyes cast in shadow from the halo behind him.

“Do you love me?” Rob breathed in, exhaled, and breathed in again. “Because I’ve been feeling this way for a while now, and I can’t hold it inside any more. If you…”

There was a long pause. Julie lifted her head to look at Rob. His lips were moving, his eyes were soft, but instead of his voice coming out, only a crackling sound emerged. It had no rhythm, and was punctuated at intervals by snaps and hisses. Her brow furrowed, and she watched his mouth. She could almost hear something being said, but she couldn’t make out any words. Julie reached out to touch his lips. She flinched back, her fingers burning.

Julie woke up on the cabin floor curled up in a ball, clutching her hand. It throbbed against her chest. The fire was still roaring, as she’d left it. She glanced around the cabin, and the table and bunks swam in her vision.

“What the hell.”

It was supposed to last for hours. It was supposed to last her until the morning, and it had only lasted what felt like ten minutes.

“What the hell?!”

She looked around for the herbal pouches. They were still there, but the file was gone. She checked her backpack, checked the floor of the cabin and the bunks. She wasn’t dreaming, she’d really burned the last of it, but instead of a final goodbye, all she’d gotten was a glimpse, a blip, a half second. What had gone wrong? Why wasn’t it working? It was the last she had of him, it had to work.

Julie closed her eyes and lay down on the floor again, willing herself back into the bedroom to hear Rob say just one more time that he loved her, that he couldn’t sleep at night, that she was the one he’d been waiting for all these years, that he wanted to know if she felt the same way, and for her to say that she did, unburdened by the yoke of all the things he’d done since that night. To hear for the first time just one more time that there was nobody that had ever meant to him what she did, and to share that she felt the same, to soak in the warm bath of love and light that was the beginning. And now the magic had failed her, though she had saved the strongest items for last.

There was supposed to be catharsis. That’s what the backdoor pharmacist had called it: “a potion of catharsis.” And here she was, drunk, with nothing left to burn except herself, the past still with its hooks in her. It was unfair. It was cruel.

And there was no one to take it out on, Rob long gone, the pharmacist a hundred miles away, so she pounded the floor. She was owed this much, and even then it was taken from her. Her hands beat on the wooden boards, beat them again and again because there was no culpable face to bury themselves in, no one to blame but herself and she was done with that, so she beat the floor ferociously, beat it savagely with both hands, the boards bending under her fists. She was making so much noise somebody within a hundred feet could probably hear her. Then, with a crack and a groan of old wood, Julie’s stomach turned as the floorboards and herself slowly tilted from horizontal to slanted to upright. Something in her mind had turned wholly perpendicular.

Newly planted on unsteady feet, Julie stands before a gorgeously stained wooden door of a very nice house. She goes back to beating on the door. A little too loud but this has to be the place, this is where the officers said that Rob lived, and his car is in the driveway, so it’s time for answers, knock knock, open up. She is going to get answers from that bastard, come hell or high water.

The stained cherry door opens to reveal a woman in her mid-thirties. She wears an apron and smelled of cut onions.

“Uh, hi, can I help you?”

“Hi, I’m looking for Rob.”

“He’s not home right now.” The woman pauses, looking Julie up and down, then extends a hand warmly. “I’m Sara, his wife. And you are?”

The warmth is unexpected. This wasn’t how it was supposed to go. She had a whole dialogue planned, a rant, a diatribe, but this woman smells like cinnamon and talcum powder. You can’t yell at someone who smells like that.

“Uh, sorry, I’m…Ruth, I work with Rob over at the office.” Julie puts on a smile and shakes her hand.

“Hi Ruth, nice to meet you. And it’s nice to finally meet somebody from Rob’s work, he’s usually so quiet about it. I think you’re the first colleague of his I’ve met in years.”

“We’re a busy bunch. It’s nice to meet you too, Sara.” This is wrong. This person seems friendly, not jealous. Not bitter. “Any idea when he might be getting back? He said he had some files for me to look over, and I wanted to get a head start on them if I could.”

“Shoot, he flew off to Houston to meet with a client. Said he wouldn’t be back until Sunday.” Sara cocks her head. Is it really work, or is he on to the next person? “Rob didn’t mention anything about leaving any files, but if you tell me what to look for, I can take a gander around his office.”

A gander. Southern. Willing to help. Either she knows everything and is somehow, in some weird way okay with it, or she knows absolutely nothing. “Uh, it should be a manila folder with a couple of memos in it. The file’s called Sanderman. It’s got copies of a contract related to our new client over in Nashville.”

How quickly the lies come. It isn’t hard when folks give you an opening. One just stacks on the next. Was that how it started with Rob? Is Julie even the first he’s lied to?

“I have to know if she knows,” she thinks in the moment. “And if she doesn’t know, I have to tell her. Men may be animals, but women don’t have to be. Maybe I can comfort her in the way I wasn’t.”

“Sanderman. Okay. Give me just a minute.” Sara moves to go in, and stops. “Oh, where are my manners. Come on in, take a seat in our living room. I’ll be back in a jiffy.”

Inside is a small atrium, with a living room to the right. Sara walks in her fluffy lion house slippers down the hallway and upstairs. On the dark hardwood floor of the living room, Julie sees a bright yellow toy. A part of her recognizes the white furniture and paint aesthetic of the room, absently notes the multiple photos of people that looked like Rob and Sara and others, but the yellow toy lurks there, tucked into the shadows under the edge of the coffee table like an animal huddled out of the rain. Julie steps inside to get a better look at it. It’s three yellow rings on a blue stand, toppled over but still on the stand like a puffy Christmas tree on its side.

She reaches down to pick it up. It’s wet and sticky.

Around the corner, there’s a soft burble. Julie freezes.

Again, the soft burble comes, this time rising and falling in breath, accompanied by a moan. It sounds like a complaint, a very small complaint without syllables. On the balls of her feet, Julie steps towards the corner to find the source.

A white basket sits on the far counter of the kitchen, a small blanket with pink elephants and yellow ducklings draped over its side. The basket rocks a little back and forth. Julie walks over to the basket. Julie gasps.

Inside is a baby dressed in a pink onesie with unicorns and dragons who couldn’t be more than six months old. The girl is awake, and staring at her, burbling. She has a cone of brown hair and green eyes that seem to know her.

It has been just over a year since she’s seen Rob. He was distant and gone more often on business the last two months before he left. Julie has scoured that period in her mind for clues as to what has caused him to leave, what little thing she has done, what might have set him off, where she might have driven him away. She touches the baby girl’s bassinet. Guilt washes down her spine like a cold, damp rag. Julie is the interloper here, and suddenly she sees herself perhaps as Sara sees her, a stranger in her own life. The longer she stays here, the more likely she is to break something.

She sets her hands on the side of the bassinet, steadying herself. Did he made the choice to cut it off because of this child? Did he change because of her? Is he really in Houston now on business, or is he back to his old games with someone new?

The baby reaches up, and grips her finger tips. Julie almost jumps out of her skin, and tries not to scream. There is not just one innocent here, but potentially three: Julie, his wife, and his daughter. Telling Sara will change all of their lives, and not just hers.

The baby squeezes her fingers. Julie shudders and stifles a sob.

“Be good, little lady. And be careful of handsome men with green eyes.”

Julie walks out silently. “That’s why he cut it off,” she tells herself. She shuts the door firmly. It has to be. He focused on his family. But he’s away on work again, what if he isn’t telling the truth? What will it take to get him to stay? Another child every nine months? What the hell is so wrong with the women in his life, his beautiful, kind wife, his adorable daughter, or even just Julie, any of them? Why can't he stay? Why?

Julie manages to make it around the corner, out of sight of the house, before she sits down on the curb and just cries. Her tears mix with the beads of sweat running down her temples. She begins to baste in the late summer afternoon there in Savannah. Finally, she stops and shivers all over, feeling disgusting and damp and discarded, like a used condom. There is a mild breeze which, when it fades, only leaves her wanting more comfort. Everything is hot. The air, her face, the concrete, even her shoes were hot.

And for a moment, something became clear to her in the dream or memory or whatever this was, in a way that hadn’t been at the time: it had never been about her. The breakup, or the hiding, or really even the entire relationship with Rob. She’d done nothing wrong. The only crime she’d committed was loving someone who didn’t seem capable of loving her, perhaps even capable of honest love at all, and that was no crime at all.

In between the sounds of a car idling by a street over, of kids squealing in a backyard somewhere, of cicadas buzzing in the trees, Julie swears she can hear the crackle and pop of a fire going somewhere. She watches as the heat waves rise from the asphalt in a blur, and she waits, knowing the memory will end at some point. She soaks in the heat of the summer day and of the fire, letting it wash over her.

•

Sebastian Salgado Flores

Total Eclipse

Elissa Barrett Cohn